Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialty computers of the '80s to the halcyon days of Windows XP.

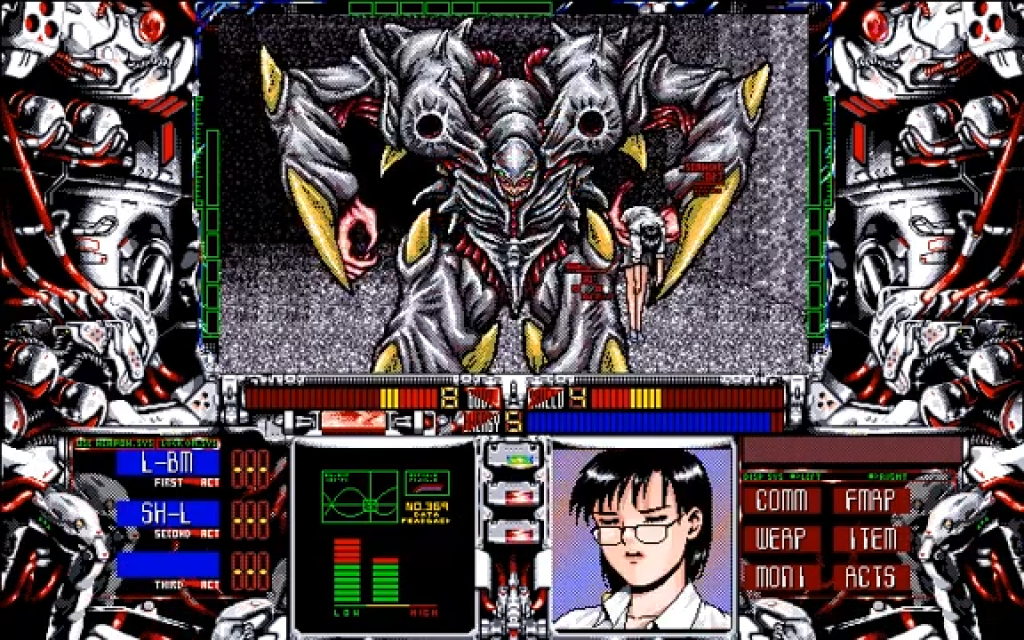

At a glance, Hamlet looks like another dungeon crawler to add to the already massive '90s pile. There's the screen-clogging user interface. There is the crude first person view. There are a bunch of stats, menus, and equipment with AWK ENG ABBRV endemic to the genre because there simply wasn't room for anything more. I might as well dust off my graph paper and get stuck in it.

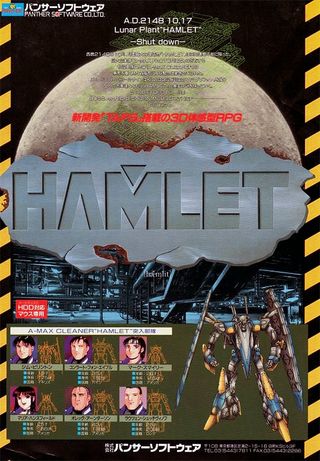

But nothing more than a quick glance shows how ambitious and innovative this game is. It's a free-roaming, true 3D, survival horror-tinged, mechanical adventure running on a line of computers that, under normal circumstances, would expect me to politely wait for loading of a large spreadsheet stored on a floppy disk. Here I am, the newest member of a small team sent to find out why Hamlet, the titular lunar installation that has certainly not done any questionable research, is not responding to any outside communications. I must scavenge repair kits and armor, retrieve vital information left behind by the dead, and use whatever weapons I find sparingly, because every shot counts. I may have access to everything from laser guns to rocket launchers, but I've never felt more vulnerable.

A constant stream of spontaneous radio chatter and unexpected events keeps me on my toes. This isn't the kind of game where nothing happens until I press a button or open a door: it's a dangerous place that's under active investigation by from the other members of my team, a place that won't wait for me to prepare. before starting to fight back.

The primitive rendering of my lunar environment really enhances the mood. A game set in a strangely lifeless lunar installation should feel dark, gritty, and intimidating. It should be impossible to see far away. Much like the fog in Silent Hill, Hamlet's look is so closely tied to the setting that it becomes part of the experience itself.

And as crude as it may sound, there is a plot of details packed into each piece. The shuttle bay opening area is a cavernous structure housing several large spaceships, one of which has its rear hatch open, its (mere) interior waiting to be explored. Large struts and beams blend into the inky shadows above, and a large ramp leads down to a narrow walkway where a small wall surrounds me on one side. Elsewhere, metal pipes and grates frequently decorate the game's corridors, floors can be pierced with deep holes, and hatches open in unnecessarily complex ways. No one would have been surprised if this was another game filled with endless right-angle mazes, but from the start Hamlet wants me to see technical conduits and deserted passages, to treat this as a setup once functional which has become strangely silent. .

I have to navigate these areas using only my mouse, clicking on different parts of the main screen to make my mecha – a VF, short for Variable Formula – move forward, backward, strafe or turn sideways . It seemed quite unnatural at first, but much like the almost monochrome view before us, this unusual restriction brought a lot of flavor. Piloting a giant robot through hostile territory should seem a bit awkward for a beginner, right?

I stopped being a newbie a few hours later when I finally understood why Panther Software had gone with this strange control scheme. It's a very comfortable way to move: I simply hold my LMB to move, and gently push my mouse to the side to turn while continuing to move forward, or briefly push the cursor a little lower if I want to take a step to the side. . I'd be happy if modern adventures included something like this.

Interaction with the buttons in the cockpit of my VF is just as restrictive, this time the mouse playing the role of my virtual finger. I love immersive touches like this. I'm no longer sitting in front of my PC, I'm in my VF, I'm manually pressing buttons to call my team, I'm switching one of my interior monitors to a very handy mini-board, or I'm changing the shape of the mecha between three different Macross. -inspired combat modes.

What's amazing is that the first-person view doesn't just do a fun little screen movement between these physical changes – it actually gets closer to the ground as I smoothly dash into the form at hand. Cruise mode's high speed, Combat mode has a distinctive visual thud when it walks, and Assault mode which sits between them has a unique exaggerated tilt when it turns.

Naturally, any abandoned facility worth exploring for dark secrets is full of high-tech security systems and a few strange monsters. These enemies (along with friends, items, and objects of interest) appear not as crude shapes wandering in the darkness but as a proximity warning on my VF's HUD, the colors becoming more intense as they progress. as I get closer. When they finally appear, the sprites are often large and always show a lot of fine detail, this contrast with their surroundings giving them a kind of macabre, extreme focus: the most complex things I'll ever see in Hamlet will probably kill me.

And they'll do it quickly too, because these battles happen in real time and my own reactions matter even more than the game's RPG-lite stat system. I have to manually block incoming shots with my own mouse-controlled shield, or switch to a weapon. I then have to manually aim at a moving or perhaps even protected target, hoping to hit it as there is a short cooldown period after each shot. This will force me to adjust my focus, change my priorities, or both.

It's a huge, exciting, almost arcade-like change from the “Click Attack to replay the same old sword swinging animation” And “Party Member 1 > Weapon A > Monster 2“scenarios that are usually found in the genre.

Hamlet is an irresistible mix of disturbing and exciting, so much so that barring a few changes in its presentation (for the worse, in my opinion), it has made the leap to PlayStation and later, the Dreamcast with its basic concepts and general design work almost intact, to the point that even vital passcodes remained unchanged. This game turns every perceived weakness, from its button-heavy interface to its short draw distance, into a strength. It still feels like a unique take on the survival horror genre, even though it came out years ago. Before Resident Evil coined the term.

A game this good deserves its day in the sun, not left abandoned on the far side of the moon.