A A little mountainous gem in a country wedged between Afghanistan and China, Tajikistan has changed a lot since I first visited it as a backpacker in 2009. At the time, landing in the small capital, Dushanbe, at 3 a.m., trekking permit and invitation letter in hand. , I was greeted by a practically deserted airport and a city lit by a few electric lights. Nowadays you can get a visa on arrival and everything is louder, brighter and faster in Dushanbe.

Countless construction sites are disrupting the capital and there have been many ill-advised demolitions of old theaters, teahouses and cinemas built during the Soviet era, causing (some) outrage. But it's hard to be too far down the city's central thoroughfare, Rudaki Avenue. Partly covered with mature trees and adorned with statues, fountains and parks, it remains one of the most beautiful streets in the city center. Asiaappearing as a sort of lovers' alley, filled with strolling couples. The artery also alludes to the country's identity.

Tajik is a variety of the Persian language and the main road to Dushanbe is named after the 10th-century master of Persian literature, Rudaki, who was born within present-day Tajikistan's borders. Along with the Koran, Rudaki's collections of poems remain the most purchased in Tajikistan. About this heritage, a Tajik friend of mine, Mirzoshah Akobirov, once told me: “For hundreds of years, our culture has had connections with Persia, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. Our culture is not and never has been Russian.”

During my visit to the British Museum Silk Roads Exhibition (until February 23, 2025) in London, I was reminded of two things: first, that the term “Silk Road” is a convenient label for sprawling geographies, blurred spiritual territories, and an evolving timeline. extending from approximately 200 BC to 1400 AD. And secondly, how integral Tajikistan was to it.

The ancestors of modern Tajiks were the famous Sogdians, who, as middlemen and long-distance traders, dominated east-west trade, their leadership peaking around AD 500. Their capital was the commercial center of Maracanda (Samarkand), now in Uzbekistan, but still with a large Tajik population today.

Silk was just a precious object – with everything from garnets and glass to ideas and religions – traveling along these vast, interlocking networks across deserts and mountains and across countless borders. And today, the romantic allure of the Silk Roads still lures travelers along its various routes, from the cities of the Caucasus and the ports of Turkey to the museums of China.

Connecting the dots of the Silk Roads is addictive and I've been doing it for years, but Central Asia still seems to be the center of everything, a place where you don't need much imagination to imagine what she once was.

In Uzbekistan, you can shop in covered markets, as merchants once did, and you can sleep in a converted caravanserai where travelers tethered their animals and rested for the night. In the morning, you can order tea made with classic Silk Roads spices, like cardamom and saffron, and drink it in chaikhanas (teahouses) which also served as informal courtrooms and newsrooms during the Silk Roads era.

During my last visit to Dushanbe, at the National Museum of Tajikistan, I observed a small gold earring in the shape of a sphinx over 2,000 years old and found near the city, as well as ancient fragments of Buddhas (British Museum exhibition the exhibition highlights the progress of Buddhism across Central Asia via objects loaned for the first time from Tajikistan). And I gazed at the murals of Penjikent, a small, welcoming town once located in the heart of ancient Sogdiana.

In a shared minibus from Dushanbe, I headed northwest to Penjikent for four hours, as I had done in 2009. As soon as we left the capital, mountain spiers appeared, steep and Densely stacked, orange marmots scattered. through the fields and women sold the ancient nomadic snack Qurut (salted dried curd rolled into balls) on roadside bends. This is a logical route since from Penjikent you can easily continue to the most idealized city of the Silk Roads, Samarkand, provided the Tajik-Uzbek border crossing is open.

The Penjikent Museum dedicated to Rudaki, who was born nearby, is worth a visit, but in reality it is about visiting the sunny “Pompeii of Central Asia”, the archaeological site of ancient Penjikent, where on a terrace are the ruins of a once important Sogdian city. and fortress.

Windblown and somewhat desolate, this Silk Roads site has yielded immense treasures, including 8th-century frescoes on display in Dushanbe (and other sections were transported to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg). Penjikent grew thanks to trade routes and its fertile position on the banks of the Zarafshan River, literally “the golden stream”, and is rightly proud of its ancient history.

Like all good Silk Roads towns, Penjikent is also home to a few decent bazaars, with stalls selling unpitted cherry jam, fresh tandoor bread and giant pots of deliciously thick yoghurt. chaka prepared with dill or radishes. If you are a fruit lover, you can also get Tajik lemons, with thin skin and smooth like plums.

Stock up on everything you want, especially if you hike around the nearby Seven Lakes, a chain of pale turquoise pools in Tajikistan's Fann Mountains that offer excellent hiking. (The last time I walked there, I saw an eagle swooping down on a tumbling kitten, no more than a few weeks after its arrival in this world. The kitten managed to escape by darting under a rock.) Although these mountains are relatively accessible, the High Pamir Mountains, or Bam-i-Dunya (Toit du Monde) on the other side of the country are not, but offer some truly wild hiking opportunities.

after newsletter promotion

One day, to reach Khorog, the gateway to these mountains, I bought the last seat on a small twin-engine turboprop plane and we climbed just a few meters from the sharp edges of 7,000 meter mountains. Another time, I went back down in a minibus and it took me 16 hours to reach Dushanbe.

A gentler adventure awaits in the town of Khujand in northern Tajikistan, surrounded by apricot trees and wheat fields, all fed by the gushing canals of the Syr Darya River, ancient Jaxartes, where Alexander the Great and his Armies once sailed and fought. . But I digress.

Silk Road enthusiasts will head not to the hills but to the Tajik-Uzbek border, where, with a little taxi planning, you can leave your Penjikent guesthouse in the morning and check into your hotel in Samarkand at lunchtime.

Since the end of the long autocratic reign of Uzbek President Islam Karimov (1989 to 2016), tourism has been booming and Samarkand, a city that fuels the imagination of the Silk Roads like no other, knows it. Few sites can compare to Shah-i-Zinda in the heart of Samarkand, an avenue of mausoleums and a sea of blue tiles dating from the 14th and 15th centuries.

Tucked behind is the old Jewish cemetery where illustrated headstones tell of the lives buried there: tailors, hairdressers and dry cleaners. Many Jews from Samarkand practiced music and performed at the courts of the emirs. Very few remain today, most having left for Israel or the United States.

Then there is the Gur-e-Amir, the mausoleum of Tamerlane, with its tiled dome rising 30m to the sky and, inside, the famous tombstone, one of the largest pieces of jade in the world. For most, it is enough to know that wherever you walk in Uzbekistan, you are following in the footsteps of the great players, Arab scholars and Chinese merchants.

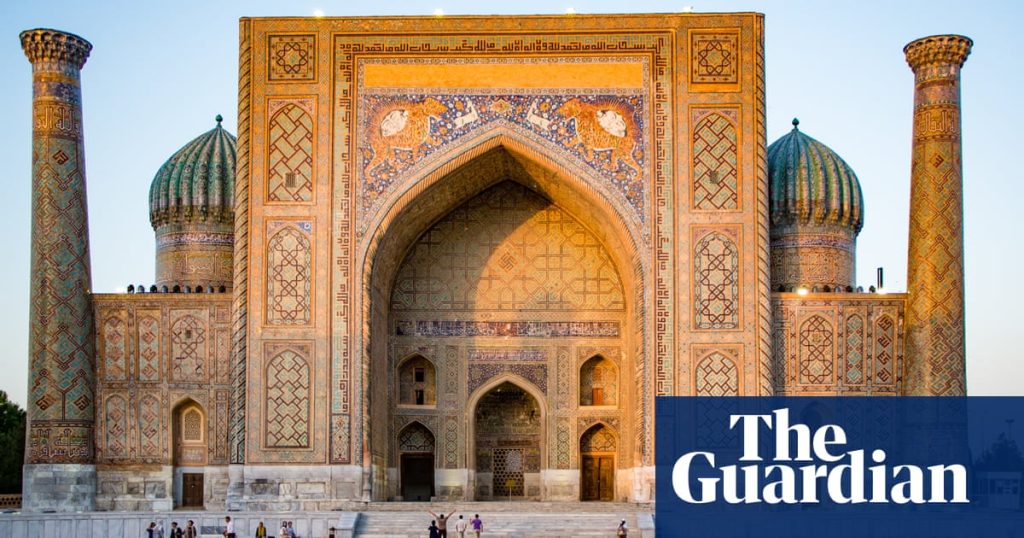

Today, there are more and more international hotel and tour bus brands with each passing year. But even as the neon lights shine on the Registan, the colossal city square with its desert-colored minarets and monumental mausoleums that was the center of Tamerlane's empire, it remains breathtaking.

All this talk of change does not mean that the atmosphere of old Samarkand has completely disappeared. In the courtyards, children fly kites and Uzbek elders sip tea under century-old mulberry trees. Hospitality is still offered freely and with great generosity and, although the cultural dynamics of trade on the Silk Roads have changed, you will find people haggling over the price of gold and rolls of beautiful colorful ikat fabrics. of the rainbow, as they always have.

Tourism in Tajikistan is in its infancy, so support local tour operators where possible. THE Zerafshan Tourism Development Association is an excellent resource for visiting the sites of the Silk Roads in Tajikistan. Sitara Travel to Tashkent offers tours of Uzbekistan.

Caroline Eden's latest book East Cold Kitchen: a year of culinary journeys (Bloomsbury, £18.99). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply