France has a bad reputation when it comes to friendliness. There is of course the long-standing cliché of the arrogant French waiter or the surly Parisian, and a Viral TikTok Earlier this year, an American woman tearfully saying on camera that traveling to France was “isolating” and that the French were not welcoming received thousands of comments – many of them agreeing with her.

“This kind of poor communication does not worry me because it is anecdotal,” explains Corinne Ménégaux, director of the Paris Tourist Office. “I think that 15 or 20 years ago, the French were less welcoming, but today we have moved beyond this cliché. You inevitably have a small percentage of people who aren't nice, and there's not much you can do about it. This is a reality in big cities, like London or New York.”

This did not prevent France from trying to restore its crude image before the arrival of foreigners. Last year, the regional chamber of commerce updated a decade-old document hospitality campaign entitled “Do you speak tourist?» in the run-up to the Rugby World Cup in Paris. The official guide discusses cultural differences, gently reminding the French that “the cultural tendency in France is to openly express one's emotions, through one's gestures or the tone of one's voice. (…) In other countries, disagreement is expressed much less openly.”

“There is still the waiter who doesn't speak to you and who, with a sullen look, serves you a Coca-Cola for 15 euros. I'm not saying it no longer exists. But we have seen a real improvement,” said Frédéric Hocquard, municipal councilor responsible for tourism and nightlife in Paris. He says the covid-19 pandemic was the big turning point.

“There was a period when we had no tourists. And the tourism industry realized that it had to make a little effort.”

Part of Paris's efforts to restore its reputation is a “hospitality charter,” which has been signed by more than 1,600 businesses in the tourism sector, from hotels to restaurants to tour guides. The agreement is structured around three main principles: promoting sustainable and environmentally friendly measures; make the visitor experience smoother; and support local businesses. Registered businesses will be able to put a sticker or sign on their establishment so that tourists know it is a trusted place. The city also trains newsstand staff, bakeries and tobacco shops to be able to answer tourists' questions.

Ménégaux and Hocquard agree on one point: visitors to Paris must also make their contribution. . In an ideal world, Ménégaux would like tourists to sign their own charter of “good tourist etiquette”. “When people come to Paris, we want them to commit to respecting certain things: respecting the peace and quiet of their neighbors, using a reusable water bottle and not buying plastic ones and not buying products made in China when you can buy local. .”

Differences in etiquette are among the first things some foreigners notice when they settle in or visit France. American expats and social media content creators Ember Langley and Gabrielle Pedriani dedicated a video to the thorny issue of French politeness in their light-hearted TikTok series, “The ABCs of Paris.” In the video, Langley warns: “What is considered polite in the United States might not be considered polite in Paris. » The two men then give advice such as “Smile less”, “Get into a debate during dinner” and “Arrive fashionably late”.

“I see Americans on the subway and it’s like I’m reading the room. Everyone be quiet! » Langley said in an interview. “When you're a traveler and you come here on vacation, it's easy to forget that 2 million people live here. You must be respectful of the local culture and approach your interactions with humility. But Langley says it's a misconception that the French are rude; It's just a matter of cultural differences. “The most important thing here is that the customer is not always right; in the United States, the customer is king.

Undercover as an English-speaking tourist

I decided to test the kindness of Parisians for myself. As a Brit who has lived in Paris for a decade, speaks French and has even obtained French citizenship (with immense gratitude), I put on my best British accent and went to see how I was treated in the French capital.

The experiment started from scratch: in front Notre-Dame cathedral, which is still blocked and under renovation after a a huge fire ravaged the roof in 2019. With a friend, I head to the archaeological museum of the crypt. “Hello! Do you speak English? I asked the woman behind the ticket counter. I was greeted with a broad smile and a patient description – in English – of the museum and ticket prices. She didn't even was embarrassed by a blatantly stupid question about the possibility of visiting the cathedral, explaining gently that the site would not be open to the public for months.

We thanked her and returned to the sun.

Next stop: a second-hand bookstore. These booksellers on the banks of the Seine must answer tourist questions on a daily basis. The man running his stall in front of the cathedral cheerfully took the time to find us some books in English, before recommending that we try Shakespeare and company just opposite, one of the most famous English-speaking bookstores in Paris. It was the same at the tourist knick-knack store, where we asked for directions to the Eiffel Tower or down to the metro station, where the woman behind the counter told us her English wasn't very good and yet she answered. valiantly to all our questions. on transport tickets with broken but determined English.

At this point, I had even abandoned my poorly pronounced French icebreaker, just bouncing off them and speaking directly in English. And yet, everywhere we went, we were greeted with smiles and a genuine desire to help. I admit I was surprised – it had been years since I had been a tourist in the city, but I certainly remember the rolling eyes, the terseness and a certain reluctance to help.

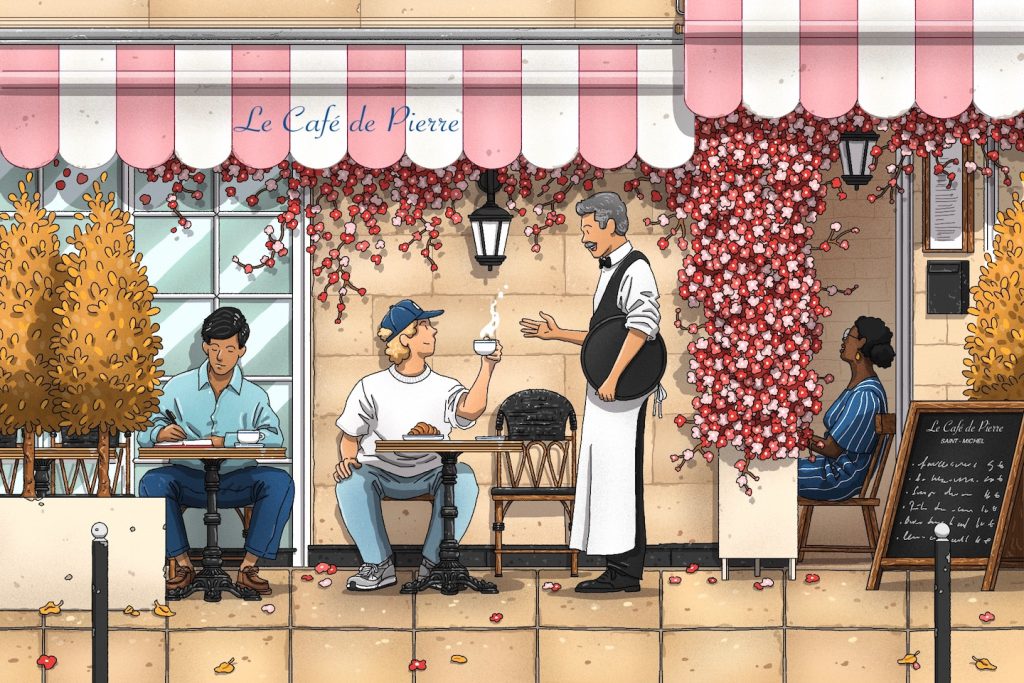

It was time for the ultimate test: ask for oat milk in a Parisian café. We chose a tourist spot on Place Saint-Michel, where the waiters were perfectly stereotypical, in white shirts and black bow ties. Our server approached us haughtily but didn't blink when we responded in English, even though he didn't understand my question at first. “Hot milk?” he repeated. When he finally understood, he laughed, waving his hands dismissively. “No nothis is not possible, soy milk, vegan milk, we don't have any, only the cow.” To make his point, he brilliantly added: “Moooo!

My request had succeeded in eliciting the famous “it's not possible” – well known to anyone who has struggled with French bureaucracy and customer service – but it was said with such good humor (and a complementary animal sound), so how could I be offended?

The dozen tourists I spoke with also had largely positive experiences. Samantha Capaldi, visiting from Arizona with two friends, told me, “We love it here,” before admitting with a wry smile, “We try to blend in, but we're so loud that everyone everyone notices us. » During the four days they had spent in Paris, they had observed the same cultural differences Langley mentioned in his videos, such as I don't have access to tap water automatically with your meal at a restaurant, or receive a funny look when you order a starter next to a main course. “They make fun of us, but not in a mean way,” she continued. “Trying to speak French helps a lot.”

Carla, from Sheffield in the UK, was in Paris with her boyfriend Brian to celebrate the anniversary of their first date. She visited Paris several times and noticed a distinct difference in the way she was treated compared to previous trips. “I'm a bit of a heavier person and have been deliberately ignored in restaurants before – other people receiving menus before me or being served before me. But I rarely get that now. Everyone seems really nice.

It seems that the efforts made by the city in recent years are bearing fruit and the Parisians, dare I say it? – learning that a little hospitality goes a long way. The only thing left is being able to buy oat milk in cafes – but perhaps it's up to Americans to let that go and rely on France's love of dairy. Mooo!

Catherine Bennett is a writer based in Paris.