Alamy

AlamyAs travelers increasingly follow social media and internet memes, the most unlikely things can become tourist attractions.

The guide said she wanted to take our photo. “To send it to Cecilia to let her know what a good thing she has done,” said the woman. “People are now coming to this small town in Spain because of his 'mistake'.”

I was in Borja, a town of 5,000 inhabitants located in the province of Aragon, in northern Spain. It was here in 2012 that an elderly parishioner and amateur art restorer named Cecilia Giménez attracted the attention of the world when she chose to retouch a fresco of Jesus Christ entitled Ecce Homo in the Sanctuary of Misericordia church which had deteriorated since it was painted in the 1930s. Giménez had initially proposed simply adding a little color to Jesus' clothing. But while the 81-year-old was working on it, she couldn't help herself: she started repainting the face.

When she took a break from her duties to go on vacation, she returned to find a crowd of shocked people and a horde of international journalists at the church. The restoration was so different that local authorities initially thought the painting had been vandalized. However, it was only the (unfinished) work of Giménez, who thought he could restore the painting to its former glory.

Instead, Ecce Homo (“Here is the man” in Latin) was renamed “Ecce Mono” (“Here is the monkey”) by the Spanish media. At first it seemed like an artistic tragedy. The image of “Monkey Christ”, as the English-speaking press put it, was omnipresent on the Internet. Memes were created. Social networks made fun of it to death. And Giménez became a hermit in her house, struck with grief by all the ridicule this caused.

Ivana Larrosa

Ivana LarrosaBut then something interesting happened: tourists started arriving in Borja. This small town which previously only welcomed 5,000 visitors a year suddenly saw an influx of travelers coming to see the botched restoration of Ecce Homo. Today, according to authorities, between 15,000 and 20,000 tourists travel to Borja each year to see the famous mistake of a portrait that now stands, like the Mona Lisa and other world masterpieces, in art, behind protective glass.

On a recent trip with my Spanish-born wife to visit family in nearby Zaragoza, I suggested we take a day trip to Borja to see the simian savior. My sister-in-law and her daughter looked at me for a moment before one of them said, “Why would you want to see that?”

Thoughtful travel

Want to travel better? Thoughtful travel is a series about how people behave when they're away, from ethics to etiquette and more.

Ever since I saw the post-restoration image of Ecce Homo, I have been fascinated by it. I couldn't explain why, but I wanted to see it with my own eyes. Like so many seemingly random things these days, it had become an unlikely tourist attraction.

Alamy

AlamyIn fact, the story of Ecce Homo is a perfect example of what, according to MacCannell, motivates many modern travelers to board a plane or train: “All tourists embody a quest for authenticity,” writes- he.

In a way, botched Ecce Homo is as authentic as it gets: an authentic, real thing born of a mistake. And as I was to discover, that’s part of the appeal of the painting.

An hour and 70km after leaving Zaragoza we were in the sleepy medieval center of Borja. The Santuario de Misericordia is located about 5 km from the central square of the city, on a hill. After paying an entrance fee of €3, the guide leads us into the chapel and there it is: the “Monkey Christ”. While we lingered, a dozen other tourists arrived to see the monkey messiah.

“MoMA in New York was interested in buying it at one point,” the guide told us. “But it would have caused too much structural damage to move it from the building.”

Giménez “was devastated by the response to her 'mistake,'” the guide added, using air quotes with her hands. “And that's why we tried to convince her that she did something very positive for the community. She put Borja on the tourist map.” She then pointed to a world map hanging on the wall. Hundreds of pins were stuck to locations around the globe from where visitors came to see Ecce Homo. There were so many in North America, Europe and Japan that you could no longer see the outlines of the countries, just the pinheads. In total, visitors from 110 countries have now come to see it.

Ivana Larrosa

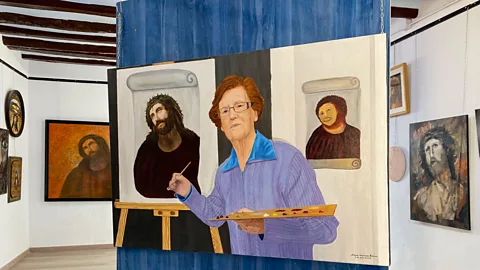

Ivana LarrosaWith Ecce Homo now behind glass and a gift shop at the exit, Borja Church has a staged look ready for tourism. As we headed towards the exit, we passed by a gift shop selling coffee mugs, mouse pads, key chains, tote bags, bottles of wine and T-shirts from the Ecce Homo brand. There was a machine that made a bronze coin with the image of the so-called Christ the Monkey. In an adjacent room, an “Interpretation Center” displayed artwork inspired by the Giménez restoration, including a photo of a person dressed in an Ecce Homo costume for Halloween and several paintings attempting to recreate the scene of Giménez restoring the fresco.

There was even a replacement photo, where you can put your face in the hole and have a photo of yourself as Ecce Homo. My wife (then girlfriend), Ivana, and I both did it and used the photo as part of our wedding invitation a year later.

When I asked MacCannel why he thought Ecce Homo had become a tourist attraction, he had a unique take on the matter, saying that the original work of art, when in pristine condition, n 'had previously attracted almost no attention. “The botched fresco was naturally not a reason for tourists to visit the church – probably not a motivator for devotees to visit.”

But by commodifying Ecce Homo and turning this particularly shoddy restoration into just another tourist attraction with entry fees, crowds and visitors taking selfies, I couldn't help but wonder if the powers that be in place in Borja were not likely to squander the unique appeal and authenticity of the place. the painting itself – the very reason I visited it in the first place. Perhaps it was inevitable, and as I would soon learn, it also had some positive effects.

Ivana Larrosa

Ivana LarrosaSince the church began charging visitors a €3 entrance fee and selling souvenirs in 2016, profits have funded new jobs within the church (such as that of the tour guide) and much of is donated to the retirement home where Giménez now lives.

A few other unexpected things have happened since the painting became a tourist attraction, including increased interest in Giménez's work. Shortly after the botched revelations of Ecce Homo, one of his own paintings sold at a charity auction for $1,400.

According to an article in the Spanish press, for several years, tourism, image rights and programs inspired by Ecce Homo have generated €45,000 in 2021 alone for the town of Borja. There was even an opera written on Giménez and Ecce Homo which premiered in the United States in the fall of 2023. During its performance in Borja a few years earlier, Giménez was present. She loved it.

After leaving the church we had lunch at a restaurant in the center of Borja. Too creamy ham croquetas (ham croquettes), fried artichokes and glasses of local Garnacha wine – previously the only thing Borja was known for – my previously skeptical sister-in-law, Pilar, and her daughter, Ara, made a surprise announcement: they have loved our trip to Borja.

“I didn’t understand why you wanted to see that,” Pilar said. “But after hearing about Cecilia’s life and seeing the picture with my own eyes, and learning about all the people from all over the world who want to come here, I completely understand now.”

As Francisco Miguel Arilla, former mayor of Borja, said, told the press: “In the end, time puts everything in its place.”