When my sister-in-law ended her summer this year with a trip to the beach, I gave her a copy of “Forgotten on Sunday” by Valerie Perrin to take home with her. This book, along with an earlier Perrin novel, “Fresh Water for Flowers,” were staples in our house this summer, something I’ve written about in a previous column.

Perrin is a common name in Louisiana, so readers might assume she’s from around here. But Perrin hails from France, where she’s won a worldwide readership with her sharply observed novels about ordinary people who find hope and possibility through far-sighted connections with others. “Forgotten on Sunday” tells the tender story of a nursing home aide who befriends a resident, a relationship that changes them both.

My sister-in-law offered me a concise review of “Forgotten on Sunday” before I opened it. “It’s great to have a real paper book that you can still see in the sunlight,” she said. Her comment made me smile, because my wife has also struggled to read her Kindle when the blinding summer sun is high in the sky.

Even the paper books I take with me on summer beach trips can be painful to read because of the glare. I prefer to read outside in the fall, when the light is nicer and the air less stuffy. Reading on the patio is best, with the events on the page accentuated by what might be happening in our yard just beyond the book on my lap.

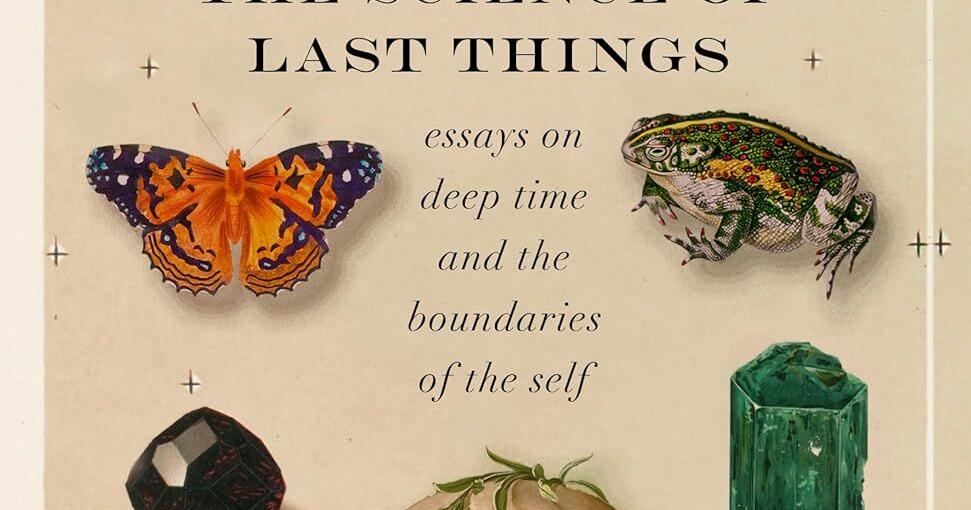

Ellen Wayland-Smith is also a patio reader, as I learned when I read “The Science of Last Things,” her new collection of essays about her life as a writer and teacher in California. As the title suggests, she addresses loss in her reflections, whether it’s the death of a parent or the prospect of her own mortality. But the book is not uniformly bleak. One of its most powerful ideas is that life is precious precisely because it is fragile.

I particularly liked the description of Wayland-Smith, who reads in his garden, while, in a nearby water garden improvised from a metal bathtub, his pet turtle climbs on a paving stone to enjoy the day. This leads to a discussion of various turtle origin myths – some of which depict the creature's shell as a punishment, while others present it as a blessing.

One of the strange problems of being human is that we sometimes have trouble deciding what is best, staying home or going away. Turtles have the best of both worlds, moving around and seeing the world while carrying their home on their backs.

In this way, the turtles may have found a bargain that we have a hard time beating. It's something I've been thinking about as fall officially arrives, wrapping up the summer travel season.

What's the best way to keep the sense of adventure alive in the fall? I do it on my deck, turning the page to see what happens next.

Email Danny Heitman at danny@dannyheitman.com.